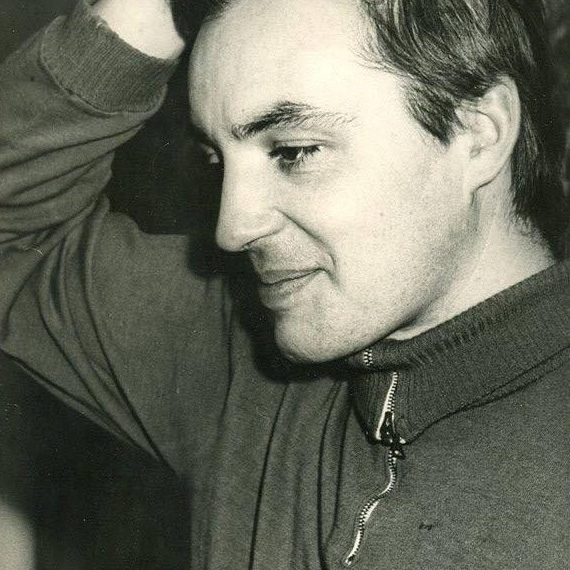

Mikhail Koulakov

Cloudless Sky

Cloudless Sky

Moscow 17 May-17 June 2007

Autobiography

I was born in Moscow on the "other side" of the Moscow river, in the old merchant’s district described by the playwright Ostrovskij in the 19th century. It is near the Tretyakòv gallery which I visited many times as a child. After receiving my high school diploma and not having any definite plans, I took the entrance exam for the exclusive Institute of International Relations and passed. This pleased my parents who were civil servants and hoped their son would make a career in the diplomatic corps. Before the courses began I visited Leningrad for the first time with an organized tour.

The architecture of Rossi and Rastrelli and the paintings in the Hermitage and the Russian Museum re-awakened my dormant ambition. Two years later I abandoned my studies at the Institute of International Relations and decided to become an artist like Repin or Shishkin.

This was followed by a period of research and wandering since my parents, disappointed by their son, refused to give me any financial support. Not knowing what to do, I entered the Military Infantry School in Vilnjus but after a year I was discharged for health reasons. I then went to work as a discharger in a medical equipment warehouse. Finally my parents, examining their consciences, managed to find me a job more related to art and placed me in the painting and decorating laboratory of Malyi Teatr in Moscow. There I worked for two years as a building painter where, during work hours, I tried to find some way of drawing and executing small oil paintings imitating Vrubel’s style. I never had a teacher in the real sense of the word and I never attended an art school to learn how to draw and paint. My teachers were my life, which imposed upon me inescapable tasks, and necessity, which continued to spur me on and ignited within me a conscious ardour and a desire to improve my knowledge.

In 1956, under the influence of Rerich and Russian icon painting, I began to do landscapes and stylised compositions. Later I was superficially influenced by cubist deformation and the surrealism of Picasso’s Guernica.

In 1957 I was expelled from the Teaching Institute (Artistic Section) because of a show organized in the home of the famous art scholar, Iljà Zyrlin.

1957 marked the birth of my personal style. Without knowing anything about Pollock, I intuitively began to use dripping in the manner of action painting. In 1959 I was enrolled in the Leningrad Institute of Theatre, Music and Cinematography in Via Mochovàja by the director, Nikolàj Pàvlovich Akimov, who taught the stage direction course. While he was on tour with his theatre group in Moscow, Nikolàj Pàvlovich visited the former home of Shaljàpin and saw some of my paintings in Zyrlin’s apartment. As a result I was admitted to the Institute in Via Mochovàja without an exam. At the time of my encounter with Akimov I was already a complete artist with my own style and I entered his school not to learn but to be able to devote myself to painting for four years in tranquillity since I had a scholarship. At the Institute I taught drawing and painting to my classmates along with the official teachers. In 1959 I discovered the art of Pollock and Tobey through reproductions in the magazine, Art News, and I realised that the American painters had metaphorically preceded me – the ideas were in the air.

One of my attempts to adapt myself to Soviet reality was my work as a graphics editor in the Sovètskij Pisàtel’publishing house and Lenizdat where I illustrated the poems of V. Sosnòra, G. Gorbòvskij and the prose of Aleksàndr Grin. I also worked as a theatrical set designer. For example, in 1967, I did the sets for The Bath by V. Majakovskij for the Theatre of Satire and Drama directed by Pluchek. Because of the strict official requirements, my work in the publishing house and in the theatres was a frustrating experience, and peaceful coexistence was impossible.

After obtaining my diploma from the Leningrad Institute of Theatre, Music and Cinematography with the highest marks, I became an underground painter who lived on occasional earning, small jobs and, rarely, from the sale of my works.

In 1967-68 contacts with American diplomats stationed in Moscow made it possible for me to sell my works regularly, earning enough to live on. The occasion that first made me known to the general public was in 1967 with the play, The Labyrinth by P. Levi staged by N. P. Akimov who commissioned me to do an abstract painting that hung on the wall of an apartment in one of the scenes.

In 1963 I took part in the collective show by graphic artists from Leningrad and as a result I was admitted to the Union of Graphic Artists of Leningrad. During 1964-65 I travelled in Siberia to Akademgorodòk, near Novosibìrsk, in the company of the poet, Vìktor Sosnòra.. He recited his poems in the presence of the Academics and the Correspondent Members of the Academy of Science while I painted the large series, The Flowers of Siberia, which was exhibited in the House of Scientists. My later shows had a semi-official character since they were not organized in places open to the general public but in institutes of scientific research. In fact, the scientists were given more liberty than ordinary mortals.

In 1966 the muse and friend of Majakovskij, Lilja Brik, inroduced me to the director of the Pluchek Theatre of Satire and Drama, who had been a student of Mejerchòld. He proposed that I work on the sets for the play by Majakovskij, The Bath, staged on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. Pluchek said to me: "Michaìl Alekséevich, I give you carte blanche, do what you think is best!" For the first time I was given full freedom of expression. During that same year, an exhibition of my works was held in the rooms of the Decoration Laboratory of the Theatre of Satire and Drama,.

In 1967 I had a one-man show in the Institute of Theoretical Physics directed by the academic and later Nobel Prize winner, P.L. Kapiza. I had met his family the year before and we had become friends. Piotr Leonìdovich and Anna Alekséevna occasionally bought my works, giving me moral and material support. Here are some comments written in the visitors’ book for the show: "Miracles have not ceased to occur in the world and the works of Koulakov confirm this…" (painter Igor’ Dimént). "Hurrah, hurrah, hurrah! What a pleasure!! IT IS NEW-ACUTE-INTERESTING" (Moscow Superior Institute of Industrial Design – Strogànovka Polygraphic Section). "A fascinating show! We only hope that exhibitions of this kind are organized more frequently and in more accessible places ..." The final opinion is that of an ex-lieutenant colonel in the KGB who then headed the personnel office of the Theoretical Physics Institute: "I regret very much that the rooms used for this art show were those of a Soviet government institute – a very influential one. The organizers of the show (author’s note: the future Nobel Prize winner L. Kapiza) should have known better. While the friends and relatives of companion Koulakov could have found another place (author’s note: where? an internment camp maybe?) to extol what does not inspire either love for work nor the spirit of abnegation that animates great endeavours. It is a shame that the artist, who seems to have received a university education in a Soviet institute, should squander his time meaninglessly instead of marching in step with those who devote all their strength to the building of communism." (13 June 1967, signature illegible).

In 1968 there was an exhibition of my works at the Chemistry-Physics Institute directed by the Academician Semionov, a friend of Piotr Leonìdovich. The two institutes, that of Theoretical Physics and that of Chemistry-Physics, worked side by side and were located near each other. But the show was closed before the inauguration. An "art expert in plain clothes" paid a visit and ordered the organizers to close the show, calling the artist by the insulting name of mystics. In spite of this, things still went well for me!

In 1969 an exhibition of my works was held at the House of Scientists in Dubna, not far from Moscow. Here, as in Akademgrodòk and Erevàn, I was grouped with Sosnòra. He recited his poems and I showed my paintings.

In 1976, after marrying an Italian from Taganròg (Southern Russia) and obtaining a foreign passport, I moved permanently to Italy. All my work from the Russian period can be divided geographically: Moscow period – 1956-1957 – assimilation and study of Russian-Byzantine icon painting. I attended the Tretyakov Gallery in Lavrushìnskij Alley. On the lower floor there were two rooms devoted to Russian icons directed by the extraordinary icon painters, Andréj Rubliov and Daniìl Chiornyj and which contained the Trinity by Rubliov. One day, seeing our great interest and admiration for the icons, an old woman came over to us (myself and Leonàrd Danìlzev). She was on guard in the room and said, "In the 1930s the French writer, Romain Rolland was here and he gazed for a long time at the Trinity by Andréj Rubliov. He was filled with enthusiasm. Did you know," she said, "where the hairstyles of Rubliov’s angels come from? He drew them from life. The angels appeared to him." It was the influence of the pagan Rerich, but even more so the icons of Andréj Rubliov and Teofàno the Greek. Later I used the whiting flash that is typical of icon painting in my abstract painting. 1957 – 1958: the beginning of my lyrical-abstract period (as defined by G. Mathieu). Leningrad period – 1959-1963, also called the Levashòvo, from the name of the village near Leningrad where I rented a shack when I studied with N. P. Akimov. This period is marked by the figurative style. There was also my sometime friendly and hostile relationship with the extraordinary painter, Evgénij Michnòv-Vojténko. We were both abstract painters and we both used building materials because of their low cost, including chipboard, nitro enamels and plaster as filling for material painting. Génja lived in Rubinstein street and I rented a room nearby, in via Kolokòlnaja (which Gleb Gorbòvskij re-baptized "Kulakòlnaja"). Our microcosm was joined by the poet, essayist and prose writer, Jura Galezkij and my school companion, Kid Kubàsov. Genja rented a barn outside Leningrad where he kept his painting materials (the smelly, inflammable nitro enamels) and wooden scaffolding for painting horizontally. Neither of them required the force of gravity and the smooth flow of the nitro enamels needed a perfectly horizontal base. On one occasion, Edik Zelënin and myself went out of the city and I suggested we take part in a happening. It was a marvellous summer day in St. Petersburg with still air and very few clouds in the sky. We took apart the wooden scaffolding Michnòv and I used, and moved it outside the enclosure. I prepared the nitro-enamels and began to pour the liquid paint onto the chipboard. Then I suggested to Edik that we run and slide down the surface of the painting on our backsides, which we did with great delight. One, two, three, and we slid, to the sound of the Sun Valley Serenade. I then set a corner of the painting on fire, igniting the nitro-enamels and fusing them, producing new, extraordinary nuances unknown to Van Gogh. However as always, there is a "but ...". Suddenly the wind came up and the fire spread to the entire painting. It was impossible to put it out and a few moments later the painting exploded. We ended up in a ditch nearby and could do nothing but contemplate the flames devouring our masterpiece surrounded by a black cloud of stinking fumes. Sic transit gloria mundi ... Later, despite the iron curtain, I managed to read a book by the American psychologist, Moreno, who proposed to transform the world into a theatre. And so the idea of the so-called concrete theatre was born, in which the actors become spectators and the spectators become actors. Our theatrical activity was unilateral. We invented some games but not having the means to realise them, the discussion ended there. At that time the word "happening" did not exist and all we could do was amuse ourselves with idea-words. In front of us was a wall covered with bricks. For a long time nothing came into our minds and then suddenly the idea appeared, right under our noses! In front of the wall were lined up a platoon of soldiers in felt boots who were assigned to manual labour. We put in front of them bowls of paint and explained what they had to do. "Dip your boots into the bowls and launch an attack on the wall, striking it with your feet". After about fifteen minutes of this battle the wall was painted no worse (and perhaps even better!) than Jackson Pollock or Georges Mathieu could have done. Another time on the suburban railway we began an absurd conversation in the spirit of Samuel Beckett in imitation of Peg and Neg. 1964-1970: works with religious subjects. At the age of 33 I had myself baptized in secret by an extraordinary person, the priest Dmitrij Sergéevich Dudko. I also painted a series of works inspired by the gospels of Mathew and John (non-canonical iconography). One of the strongest works from this series is in the collection of G. D. Kostaki. Second Moscow period (1973-1976) For two summers I worked on the shore of the Black Sea, in Gelendžìk, where I embraced the natural marvels of the south. The result was that in many of my works you can discern the ancient wind of the Taoists. I painted the spring, the peach blossoms, the rocks, the sea, the sky and the pine trees. Seize the fleeting moment, you are so beautiful! (as Goethe said). But, unfortunately, that is impossible. It seemed to me that artistic creation was theurgic and more real than the phenomenal life. Perhaps I still think that way now. The last period, the Italian one, began at the moment of my departure from the Soviet Union in April, 1976. When it will end is known only by the great architect and art scholar, Piotr Naùmovičh Palzev, who is writing my biography. ( translated by Adrian James )

Critical notes

"…Expressiveness, an orgy of colors, freedom of expression coexist in the artist’s work with a precise rendering of the individual characteristics of each plant, leaf, flower…" K. Bushkin, The flowers of Siberia " Za nauku v Sibiri", Novosibirsk, 1 January 1965

"…His small-scale gouaches have dynamism and spatial substance almost like a fresco; viewed together they are imposing and rigorous, just as frescoes are…" Tatiana Panchina, Exhibitions of the avant-gard in Paris with the participation of Russian artists, "Russkaja mysl", Paris, 18 August 1977

"… Mikhail Koulakov is an artist of considerable talent. Looking at his works, even if one sees echoes of European and American influence, like Jackson Pollock, but this is no help in understanding the painter’s character. His works are highly original and expressive. They stand out for the diagonal tension of the compositions, and the intensity of the colours creates an avalanche effect…" Tatiana Panshina, Russian painters at the Fall Salon in Paris, "Russkaja mysl", Paris, 4 January 1979

…" As I understand it the art of Koulakov creates freedom with the many expressions of textural painting: the colors, the plaster, the metal, the unusal chromatic compositions similar to distant flashes of lightening (yes, distant flashes of lightening because I have seen so few in my life), the attempts to exceed the traditional dimension of the painting, the images, the jarring view of natural alterations, the movement of the hand, the gesture of the artist and his work as an act, a message, as something which is in constant formation, now fast now slow…" D. S. Likhaciov, the catalogue of the first exhibition in the Soviet Union, the gallery of the Soviet Foundation of Culture 1989-90

" …One of Koulakov’s unique traits has always been a perseverance and consistency of artistic investigation. Each step in the creation of form is pondered, considered and deeply felt, and his spontaneity can be seen as an unexpected action in an otherwise rigorous system of figuration, rather than just the result of chance enlightenment. For Koulakov the artistic experience of other painters ( he often cites Pollock, Tobey and ancient Russian art) never results in reinterpretation or imitation, but rather serves as a pretext to affirm his own independent thought. For this very reason perhaps already in its phantom existence the art of Koulakov was not intended as an unrestrained polemic as an end in itself, but as a personal interior meditation where the artistic form meant essence of life . This type of meditative art usually makes the life of an artist difficult; it leads to isolation, but at the same time it lends a philosophical depth to the work…However, it is neither the chromatic value nor unique composition of Koulakov’s painting which makes them an autonomous whole. His works have something which at first sight does not appear to be so important, but which gradually moves into the foreground to reveal the rich imaginary of the artist’s world. Already in his earliest works Koulakov tended to destroy the two-dimensional surface. The buildup of the chromatic layers, the use of bitumen, plaster and nitroenamels applied layer upon surface upon layer, created a sort of relief. The image was formed on the surface and than projected into three-dimensional space. This new representation of pictorial space led Koulakov to the creation of multi-paneled painting constructions which took possession of the surrounding space, including that of the spectator, forming a type of microcosm. These constructions do not improve on nature but rather transform it into a personal, fantastic ad uniquely dynamic world of colors and spatial confusion- a world of objects and not of illusion…" Vladimir Goriainov, catalogue of the exhibition at the gallery of Soviet Foundation of Culture, Moscow 1989-90

"…The artist moved to Italy in 1976, and since then has developed in an original way his preceding experiences, which displayed a contemporary pictorial vocabulary closely tied to the intellectual and popular Russian tradition. While working in Rome the artist gave vent to his imagination, not only strengthening the connection with this roots, but also looking towards the Far East, clearly an important component of Russian culture. Koulakov resolved the risk of loosing his identity when he moved from the place of his development and his earliest maturity by searching deeply within himself and finding a broader perspective. Thus, paradoxically, after his arrival in Rome instead of Westernizing, or selecting Western models of the avant-garde, the artist in a certain sense Easternized. Indeed, even if he brought to the Italian and West European environment a cultural diversity, albeit always consistent with the common language of the avangarde, primarily of stroke and gesture, in reality he developed within this environment a style which only his Russian past could have motivated. His view towards the East offered him an ideal place for the contemplative activity and the maximum spiritual density; with the suspended time of the pure event of spiritual epiphany. Koulakov’s work does not represent only the joining of the Eastern and Western European artistic culture but, through his own Russian Orientalizing, it represent within the European artistic culture, a spontaneous recovery of the broadest traditional dimension, an acquisition of that Eastern dialogue, primarily based on the Zen behaviour and philosophy…Koulakov’s Informel style develops in reference to the stroke as icon, densely built up with colour and rapidly gestural…And it is indeed during the second half of the 1960s and the early 1970s that Koulakov’s gestural application of paint reaches its maturity and is able to offer highly suggestive results, as for example Madonna-Penelope of 1971, exhibited in Venice in 1977 in the exhaustive exhibition New Soviet Art. A Non-Official Perspective. Or for example in Madonna of 1972, where materially concrete hands emerge from a figure which is barely perceptible as pure silhouette against a textured and gestural background…." Enrico Crispolti, catalogue of the exhibition at the gallery of the Soviet Foundation of Culture, Moscow, 1989-90

At the inauguration of the same show in Moscow, his friend, academician Serguei Kapiza, had this to say: "…Mikhail Koulakov’s loyalty to his principles enables us to view his works as an image reflecting the world today. As a personality and as an artist, he was ahead of his times. He was decisive in his research and courageous in his choice of career path. Maybe this is why it is easier for us to appreciate him today because, back then, his works reflected what the world has now become, as we can see for ourselves in his paintings."

"…To my mind, Mikhail Koulakov is an almost legendary figure linked to the discovery of new art…" Leonid Bazanov Koulakov the Outsider, catalogue of the exhibition Sinergy of gesture-sign-symbol, The State Gallery of Fine Arts A. S. Pushkin, Moscow 1993

Marina Bessonova, curator of the exhibition at the State Gallery of Fine Arts A. S. Pushkin, Moscow 1993, wrote: " …The incontrollable running riot of the spontaneity of colour, already characteristic of the early Russian avant-garde, that without doubt was vividly embodied in Koulakov’s abstractionism, is united in his art to the discovery of the sculptural sign as a prototype, the materialised archetypical symbol, which actually takes Koulakov’s abstractionism outside the boundaries of the traditional painting dimension…"

"… MK , victim and hero of one of the first public scandals associated with the . establishment of abstract art in Moscow art life notwithstanding all prohibitions. In this collection is represented an excellent work of this master possibly the only pioneer of abstraction during the Thaw period to preserve his loyalty to this art form. In this work of the transitory period the energy becomes introvert…" Bar- Ger Collection and the Russian underground, Aleksander Borovsky " The non –conformists, the second Russian avant-garde 1955-1988", 1996